Last summer, Steve Bodi was walking across a cattle ranch in Montana with just three days left to his trip. He was looking for a clue of buried treasure and as luck would have it, he noticed a small piece of bone sticking out through a rock.

As he scratched around in the dirt, he found it wasn’t small, but instead a four-foot long leg bone. He continued to dig and hit another bone, then another. All in all, there were 10 pieces uncovered in those few days. He had to preserve his discovery in order to return home, so while he won’t be able to verify it until this summer when he can make his return trip, he believes those bones belong to a triceratops. This wouldn’t be the first dinosaur fossil that Bodi has dug up, but it could be his first triceratops.

BITTEN BY THE DINOSAUR BUG

Unlike most paleontologists, Bodi didn’t find himself in love with dinosaurs from a young age. He was, however, fascinated with fossils, rocks or pieces that give someone a glimpse of the distant past. As an adult, he owned a business, Renaissance Rentals, as a real estate developer who built and managed rental properties in Bloomington.

It wasn’t until 2010 that he discovered his passion for dinosaur fossils. His brother-in-law Mark Tarner shared how when he was on a business trip in Montana, a cattle rancher teased him about how there’s dinosaur bones just poking out of the ground of his ranch. Tarner thought it was joke, but he went to the ranch and sure enough, there were bones clearly sticking out of the ground. At long last, he convinced Bodi to join him on a trip to dig for fossils.

“I finally relented,” Bodi said. “He knew that I was in trouble because that very first day, we were in South Dakota in May and it was spitting snow, 32 degrees, freezing cold. I was hunched on the ground picking up every little scrap. People were teaching me, that’s a dinosaur bone, that’s this or that, for hours and hours. At the 10th hour, people were ready to go and I’m still hunched over, not ready to go yet. I had been bitten by the dinosaur bug.”

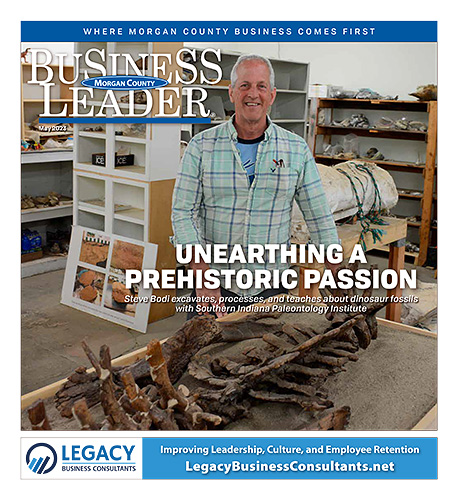

Bodi founded his nonprofit Southern Indiana Paleontology Institute in which he not only excavates and cleans up the fossils he’s discovered, but also teaches and trains interns to do the same. The operation is entirely self-funded and he does not Steve Bodi excavates, processes, and teaches about dinosaur fossils with Southern Indiana Paleontology Institute sell any of his finds. He has donated pieces to individuals and museums.

“Our purpose, our reason for being, is to enjoy the whole process of discovery and research,” Bodi said. “To date, some people have talked to me about it or tried to donate, but right now I’m still doing it almost like a hobby but it’s so outgrown a hobby.”

FOSSILIZED EDUCATION

Bodi said he’s in a bit of a niche because his institute isn’t connected to a university or museum and isn’t done for commercial purposes. He has met paleontologists who work at The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis who he said have been quite generous in helping him along his journey into the world of dinosaur fossils. In the beginning, he would take specimens that he found in to the lab at the museum and they would give their critique and advice. They’ve gone on digs together and continue to share pieces of education about current findings.

In 2015, Bodi started taking in high school and college interns, unpaid, who keep to a routine schedule and work to learn the techniques of how to prepare and clean fossilized bones. His collection of fossils had grown too large for him to keep up with himself. The interns start with smaller pieces and work their way up to more prized dinosaur specimens. Some of those interns go on trips as well to experience the discovery and excavation side of the field.

Bodi sold his rental company in 2018. He still owns properties, but he no longer runs the management side of the rentals. This has allowed him more time to focus on his passion for paleontology. Last year, he began teaching a course on paleontology at Franklin college, where students get to start with something in a plaster field jacket, something resembling a finished piece one would find at a museum. A field jacket is the manner in which paleontologists preserve pieces for transport by covering them in a plaster and burlap material.

Read the Full May 2023 Edition Here